Images by Mariëlla van de Stolpe

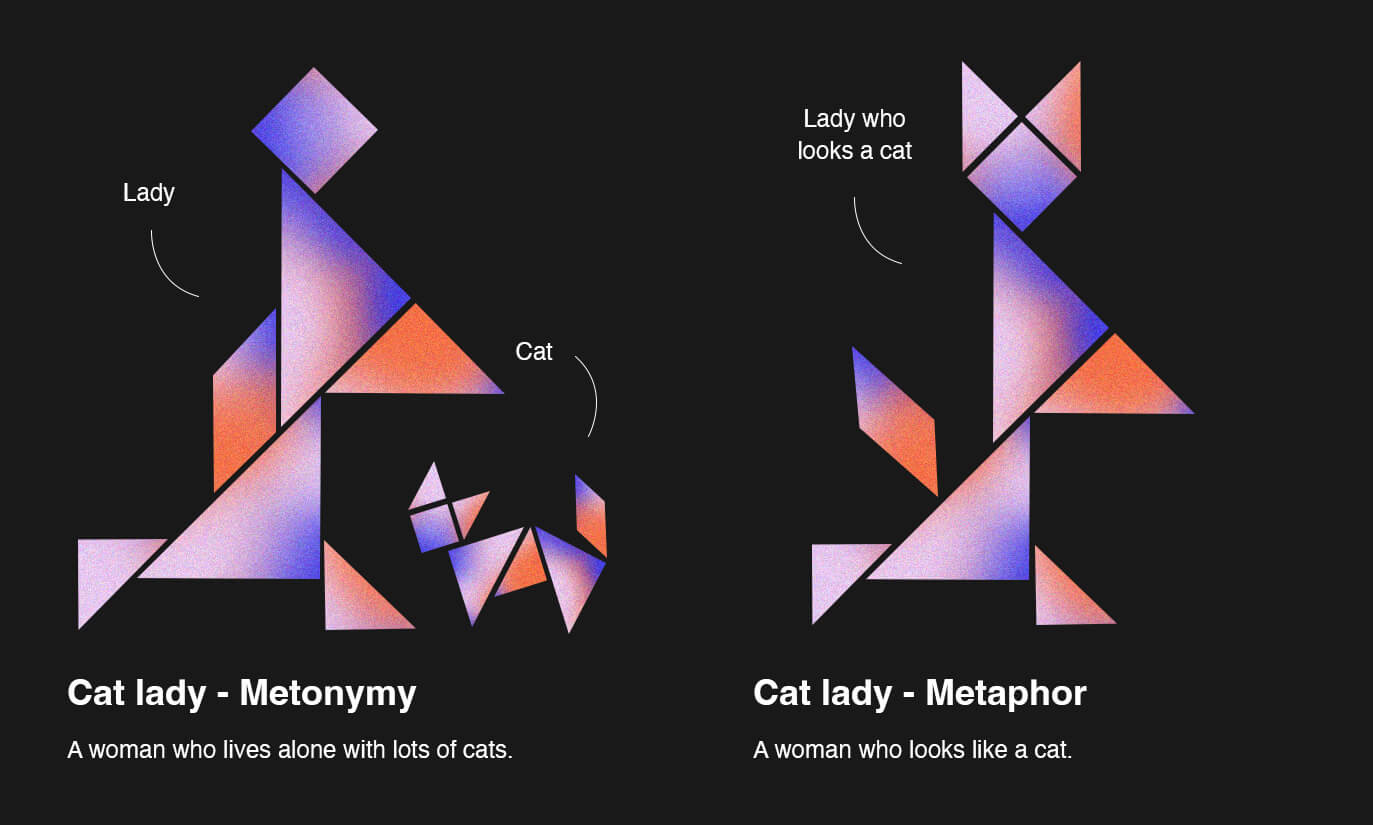

Like with all types of accessibility concerns, there is a whole range of potential recipients with a certain impairment present in different degrees, from barely noticeable to the extreme. In the case of understanding metaphor and metonymy issues, these extremes are called similarity disorder and contiguity disorder.

People who do not understand metaphor suffer from similarity disorder:

- They struggle when they need to replace one word with any of its synonyms or heteronyms (corresponding words from another language).

- They have difficulties understanding different dialects of their native language.

- Context plays an important, often crucial role for them

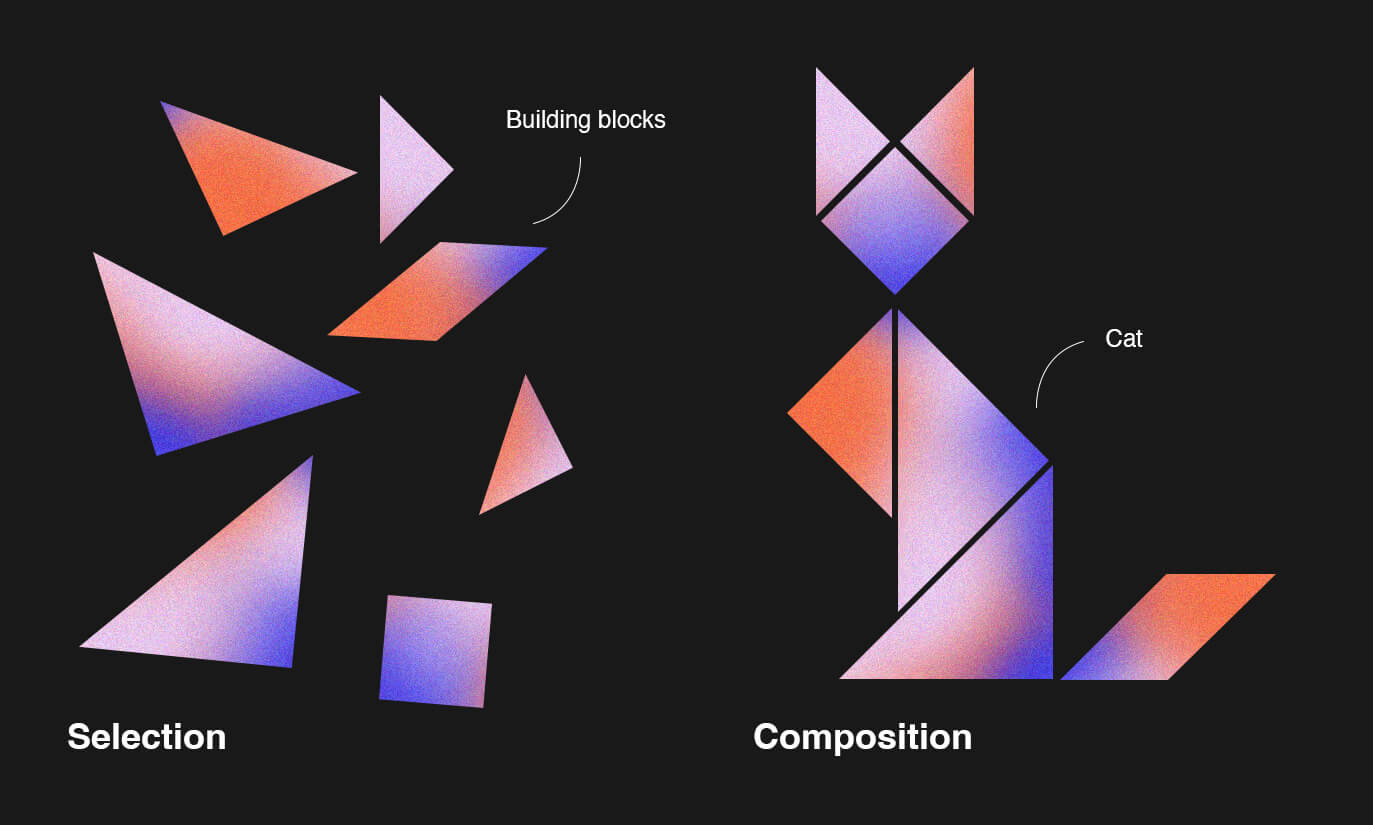

- They can’t understand building blocks in isolation, but they can easily see how those blocks fit together.

- Since their sense of a metaphor is impaired, people with similarity disorder often use metonymy as a communication device. For example, if they don’t understand the word “cat”, they might refer to it with an expression like “it catches mice”.

On the other side of this spectrum are people with contiguity disorder, who struggle with metonymy:

- They give little or no importance to the context and word order.

- They can understand isolated building blocks better than the arrangement of such blocks.

- When learning new words, they tend to ignore their derivates.

- They instead see compound words as unique without noticing the parts they were made of.

- They adopt new vocabulary easily, but they struggle with grammar, especially declension, conjugation, and other types of inflection.

- They often omit context-related words, such as conjunctions and prepositions, unlike the opposite group, which relies on such words.

Important is that between these two extremes lays the whole range. Think about what makes it difficult for you when learning a new language. If it’s grammar, you are a more “metaphorical” type of person. If it’s vocabulary, you are more “metonymical”.

How can these insights help us write and design more accessible content?

Does this all mean we should drop metaphors or metonymies? Certainly not. But we should acknowledge the difference between the two and be aware that there are people who have difficulties understanding one or the other. Here are just a few things you can do out of the box (which is a metaphor) and a few no-nos (which is a metonymy):

Metaphors are often used in inappropriate language:

- Be careful when referring to people as animals or associating animal-like characteristics with individuals, even in a positive context, such as “heart of a lion” or “faithful as a dog”.

- Don’t call anyone a “design bullseye” or “grammar Nazi”.

- Avoid metaphors that can be easily misinterpreted. For many readers, a “smashing design” or “killer logo” can sound unnecessarily violent.

- Avoid overused metaphors like “tip of the iceberg” or “needle in the haystack”.

- Avoid metaphors with too broad meaning, like “making a design pop”.

Metonymies are, on the other hand, often used in unfair generalizations:

- Avoid replacing the whole with the part – don’t call Great Britain “England” or The Netherlands “Holland”.

- Don’t use it the other way either – avoid using just “America” as a name for the United States.

- Similarly, avoid using brand generalizations, like “Googling”, “Skyping” or “Photoshopping”.

- Same, but much worse, is the use of “generic masculine” pronouns. Saying that you care for “a user and his needs” is wrong for the same reason as addressing the whole group of people as “guys” – it is poor metonymy.

Again, if all this looks like suggesting yet another limitation to the copywriter’s creativity, it really isn’t. On the contrary, both metaphor and metonymy help make your content more accessible if you use them the right way. It applies to both accessibility and inclusivity, which aren't mutually exclusive.

In one of the following articles, we will discuss how metaphor and metonymy reflect in visual content, from Rembrandt’s paintings to icons on a website. You choose whether to stay tuned (metaphor) or to keep your eyes peeled (metonymy).