Discover industry-specific solutions and expertise.

Solve your toughest A&D challenges with Belcan.

Ignite peak performance and efficiency in your business.

Reimagine your manufacturing competitive advantage.

Accelerate growth with customer-focused solutions.

Our data and AI solutions align with your business outcomes and create impactful results.

Personalize learning experiences with education tech and IT solutions—and make learners feel valued.

Create strategies for product, service and process innovation that deliver new growth.

Meet customer demands for a digital, personalized online insurance experience—while reducing risk.

Digitally transform to empower a more intelligent, agile and high-performing enterprise.

Make business decisions based on real-time contextual data with our digital solutions.

Stay ahead of the competition with the latest tech like IoT, machine learning and blockchain.

Deep industry expertise to propel your business into the future.

Explore Belcan’s flexible, custom-tailored solutions.

Solution to turn isolated AI pilots into production-grade agent networks.

Put AI to work and turn opportunity into value.

Accelerate time to value for industrial edge AI.

Maintain high integrity across the AI lifecycle.

Realize the next frontier of enterprise performance.

Enhance operations, boost efficiency, remove technical debt and modernize apps for the future.

Boost operational efficiency, optimize costs and speed product development.

Transform operations through intelligent orchestration, platform integration and strategic partnerships.

Enable a more secure and value-centered business with proven next-gen solutions.

AI insights to inspire enterprise transformation.

Set your modernization up for success with a flywheel strategy.

Develop the technical capabilities needed to create robust agents.

Bridge the gap between strong AI leadership and business readiness.

Explore the latest in AI in our newsletter released bimonthly.

Dive into our forward-thinking research and uncover new tech and industry trends

Explore the top focus areas that are important to Cognizant and our clients.

Explore how our expertise can help you sense opportunities sooner and outpace change.

Discover industry-specific solutions and expertise.

Solve your toughest A&D challenges with Belcan.

Ignite peak performance and efficiency in your business.

Reimagine your manufacturing competitive advantage.

Accelerate growth with customer-focused solutions.

Our data and AI solutions align with your business outcomes and create impactful results.

Personalize learning experiences with education tech and IT solutions—and make learners feel valued.

Create strategies for product, service and process innovation that deliver new growth.

Meet customer demands for a digital, personalized online insurance experience—while reducing risk.

Digitally transform to empower a more intelligent, agile and high-performing enterprise.

Make business decisions based on real-time contextual data with our digital solutions.

Stay ahead of the competition with the latest tech like IoT, machine learning and blockchain.

Deep industry expertise to propel your business into the future.

Explore Belcan’s flexible, custom-tailored solutions.

Solution to turn isolated AI pilots into production-grade agent networks.

Put AI to work and turn opportunity into value.

Accelerate time to value for industrial edge AI.

Maintain high integrity across the AI lifecycle.

Realize the next frontier of enterprise performance.

Solution to turn isolated AI pilots into production-grade agent networks.

Enhance operations, boost efficiency, remove technical debt and modernize apps for the future.

Connect your processes, people and insights across the enterprise with AI-enabled IPA.

Turn big visions into practical realities with expertise that takes you further.

Boost operational efficiency, optimize costs and speed product development.

Transform operations through intelligent orchestration, platform integration and strategic partnerships.

Enable a more secure and value-centered business with proven next-gen solutions.

Build the software of tomorrow at speed with a focus on business impact.

AI insights to inspire enterprise transformation.

Set your modernization up for success with a flywheel strategy.

Develop the technical capabilities needed to create robust agents.

Bridge the gap between strong AI leadership and business readiness.

Explore the latest in AI in our newsletter released bimonthly.

Keep up with the trends shaping the future of business—and stay ahead in a fast-changing world.

Dive into our forward-thinking research and uncover new tech and industry trends

Explore the top focus areas that are important to Cognizant and our clients.

Explore how our expertise can help you sense opportunities sooner and outpace change.

Written by Luka Stanisavljević

08 August, 2023

Share

9 mins

At Cognizant Benelux, we try hard to make the content we present to our users understandable. Let’s elaborate on how two main figures of speech – metaphor and metonymy – can help to be clear and concise, and how they can have adverse effects if used incorrectly.

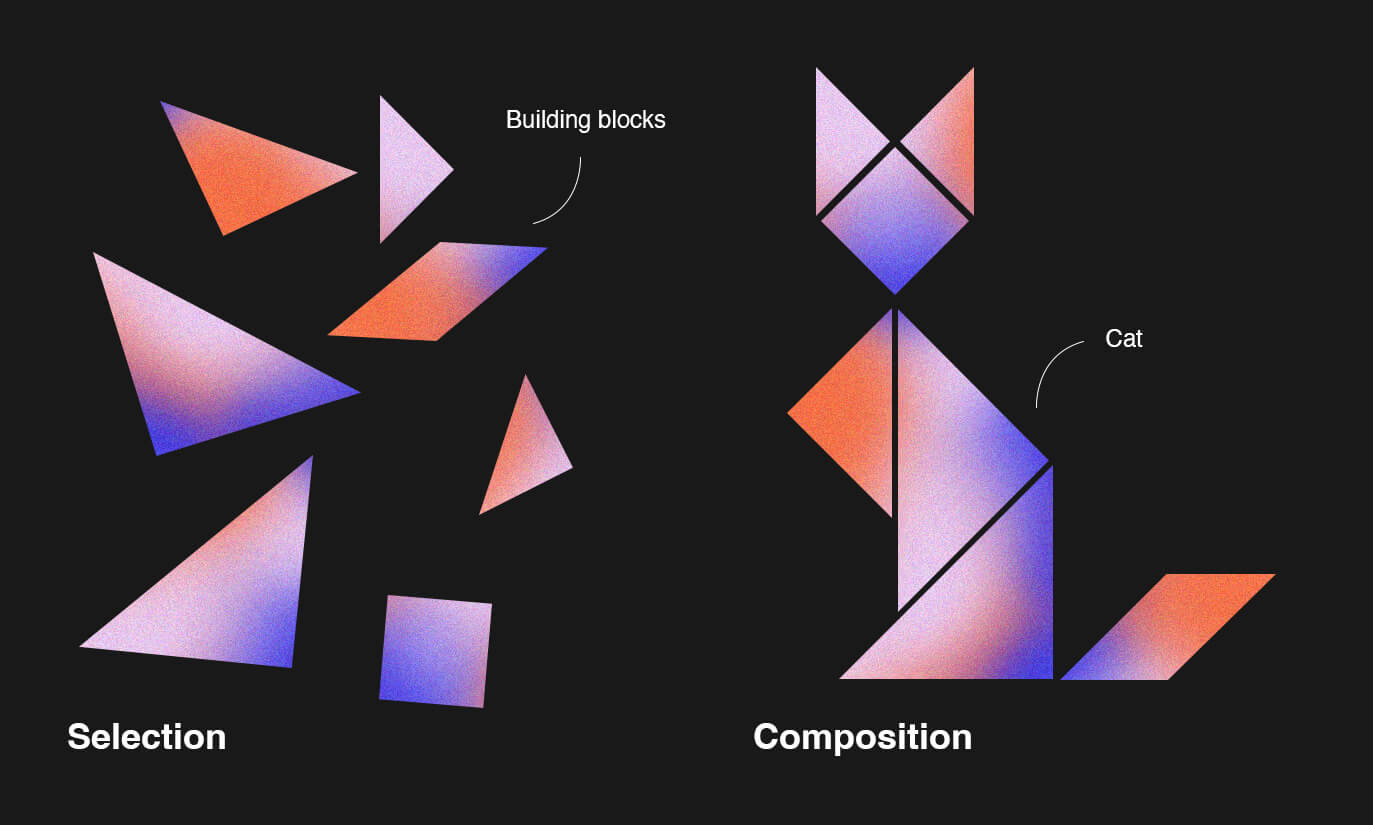

Why are these two figures of speech the main ones? Because they are the basis of two main mental processes on which every creation relies: selection, which provides basic building blocks, and composition, which puts them together. It is important to understand how each of them works, because individuals have different abilities to perceive them; therefore, understanding the distinction is essential when writing content with cognitive accessibility in mind.

Images by Mariëlla van de Stolpe

Metaphor is the first figure of speech that comes to most people’s minds. It replaces one word or expression with another, to make it more understandable, interesting, or memorable. It relies on comparison and similarity. For example, Virginia Woolf calls the human mind “the most capricious of insects”; referring to something abstract by comparing it to something visible.

But metaphor isn’t only a writer’s tool. Jargon of the street, office, news media, sport, or even product development, includes metaphors too:

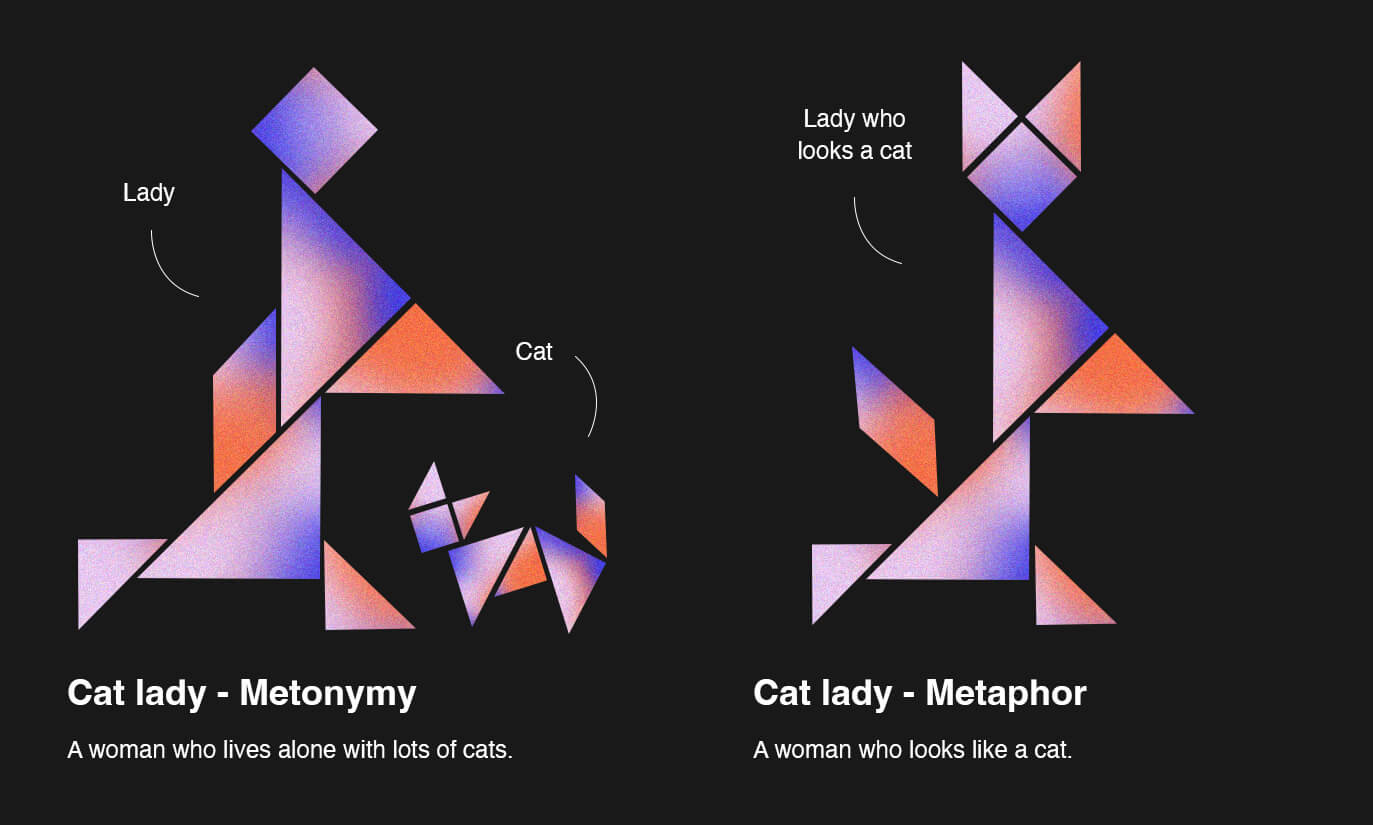

Metaphor has a less-known, but equally widely-used sibling, called metonymy. They are both used to make content either more memorable or easier to understand. But it is important to grasp the difference, because different mental processes drive them.

Metonymy doesn’t compare to anything else but replaces the word with something from its own context. For example, the tool with the tool’s purpose, part with the whole, verb with the corresponding noun, and so on:

Metaphor and metonymy aren’t just two figures of speech. They are fundaments of two different ways of perceiving the world. Linguist Roman Jakobson wrote an influential essay in 1956, in which he researched two types of aphasia, reflecting on the lack of understanding of either metaphor or metonymy.

Images by Mariëlla van de Stolpe

Like with all types of accessibility concerns, there is a whole range of potential recipients with a certain impairment present in different degrees, from barely noticeable to the extreme. In the case of understanding metaphor and metonymy issues, these extremes are called similarity disorder and contiguity disorder.

Important is that between these two extremes lays the whole range. Think about what makes it difficult for you when learning a new language. If it’s grammar, you are a more “metaphorical” type of person. If it’s vocabulary, you are more “metonymical”.

Does this all mean we should drop metaphors or metonymies? Certainly not. But we should acknowledge the difference between the two and be aware that there are people who have difficulties understanding one or the other. Here are just a few things you can do out of the box (which is a metaphor) and a few no-nos (which is a metonymy):

Again, if all this looks like suggesting yet another limitation to the copywriter’s creativity, it really isn’t. On the contrary, both metaphor and metonymy help make your content more accessible if you use them the right way. It applies to both accessibility and inclusivity, which aren't mutually exclusive.

In one of the following articles, we will discuss how metaphor and metonymy reflect in visual content, from Rembrandt’s paintings to icons on a website. You choose whether to stay tuned (metaphor) or to keep your eyes peeled (metonymy).

References:

1. Woolf, Virginia. (1953) A Writer's Diary. Edited by Leonard Woolf. Oxford University Press, 2003.

2. Jakobson, Roman. (1956). Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances. In Jakobson, R., & Halle, M. (Eds.), Fundamentals of Language (pp. 27-87). The Hague: Mouton.